In late 2007 we arranged the debate with Dr. Ehrman for January 21, 2009. The e-mails plainly included the issue of textual variation and inspiration, as we advertised the debate with that title for nearly a year beforehand. We learned later that Dr. Ehrman does not read e-mails very closely or carefully, for only a month before the debate he informed us that his conclusions regarding inspiration “are not debatable,”despite appearing in the introduction of his book, the conclusion of his book, and in almost every public talk he has given on the subject for the past three years. He insisted that we could only debate “Does the Bible Misquote Jesus?”Our phone conversation was significantly less than cordial at that time, with Dr. Ehrman derisively laughing, for example, when I mentioned the concept of Scripture as “theopneustos,”the term Paul uses at 2 Timothy 3:16. He interrupted me in mid-sentence with laughter. “Oh come on! Theopneustos appears a single time in the New Testament, in Paul. It doesn’t appear in Matthew. It isn’t in Mark, or Luke.”I truly had to bite my lip to keep the debate on track at that time, but I did so for the reason that his books are used as texts in many colleges and universities across the United States, and so I had to keep my eye on the “big picture”and the usefulness of the debate in the years to come.

So as I went into the debate on the 21st I had the following goals:

- Demonstrate that one who holds to the highest view of Scripture and its inspiration can look at the very same data and still present a strong, compelling case for the preservation of the text of Scripture over time.

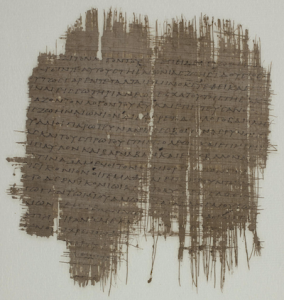

- Expose the presuppositional nature of Ehrman’s insistence that we must possess the originals for inspiration to be true. This would include making sure it is clear that when Ehrman says “We don’t know what the NT said”he means “We do not have photographic reproductions of the originals.”I desired to make sure the listener would see that the NT manuscript tradition is more than sufficient to provide the original readings, even in the toughest of variants.

- Reverse Ehrman’s “spin”on the state of the text, which involved putting a context to his constant repetition of the claim, “There are more variants than there are words in the New Testament.”

- Present a strong case for the providential preservation of the text through the explosion of early manuscripts and the lack of editorial “control”in contrast with the Islamic theory of preservation. Given that the majority of attacks upon the NT today come from those alleging some kind of controlled editing of the text, this element is vital.

- Finally, expose the radical skepticism of Bart Ehrman’s position, which leads to an abandonment of any meaningful knowledge of history itself. I needed to contrast Ehrman’s post-modernism with the viewpoints of the past, including contrasting his position with the great names in the field of the past like Tischendorf or Aland.

So how did the debate go in light of these goals? Quite well, in fact. Surely, for those looking for blood and guts such an encounter could not possibly satisfy. The topic was too wide, the subject matter too challenging, for there to be much chance of any “gotcha”moments or “clear victors.”But each of the above goals was accomplished and that with great clarity. Specifically:

- Dr. Ehrman did not even attempt to mount a case against my presentation, preferring to rely upon arguments from authority (“Well, nobody really believes that anymore!”) rather than providing counter-examples.

- Ehrman was clearer than I have ever heard him in repeating his mantra that without the originals, there can be no inspiration. When challenged, however, he kept repeating himself. He did not show any ability to go deeper into the nature of his position, and did not seem willing to examine the presuppositions behind his statements.

- It was not difficult at all to present portions of the mountain of evidence that demonstrates the unity and accuracy of the NT manuscript tradition. However, Dr. Ehrman seems to be so insulated from any discussion of the similarities of the manuscripts (and so averse to taking the time to study what his opponent has written on the subject so as to have some background upon which to work) that he seemed completely lost by the discussion of how much alike even the most divergent manuscripts are. This led to some wasted time, especially during the cross examination, for I had to try to explain my presentation to him. I have often commented on the fact that liberals such as Ehrman (Spong, Lynn, and others I have debated) do not believe it is relevant to prepare for debates by familiarizing yourself with the views of your opponent.

- I succeeded in making the case against any kind of edited control of the text and in demonstrating that this is a far more serious allegation than Ehrman’s “we need the original”argument. Ironically, Ehrman even accused me of likening him to a Muslim at one point, though I did no such thing. I simply demonstrated that the demand he makes of a variantless manuscript tradition partakes far more of the Islamic view of Scripture than the Christian one. He had no meaningful response to this, other than to confess that he, as the head of the department of religious studies at a major university, knows “little”of Islam, and almost “nothing”about the Qur’an.

- I do not believe Bart Ehrman has ever been quite so forthright publicly in his disagreement with the great scholars of the past, in his promotion of an abandonment of the establishment of the “original”text, his rejection of the tenacity of the text (though he provided not a single rebuttal to the documentation of tenacity provided by Kurt Aland) and in essence the open proclamation that we do not, in fact, “know”what anyone in the past actually said or did. When a scholar like Ehrman has to take his theories to such an extent just to avoid the authority of the New Testament, that speaks volumes.

I also believe the debate produced a number of other statements that will be most useful in the future. Ehrman’s clear affirmation that the New Testament has the earliest and best attestation of any ancient document should be made into t-shirts to be given to all freshmen college students.

So when Joel McDurmon posted his review I was left a little confused as to how he came to the conclusions he did. I would imagine part of the problem is that Joel is not overly familiar with the primary elements of my work that would give him some important background upon which to work in forming his review. Those who have read Scripture Alone, The King James Only Controversy, and have listened to my debate with John Dominic Crossan on the historical reliability of the Gospels, would be in a better position to follow the line of thought.

In my next posting I will address the assertion that this debate “proved little beside the limitations of evidentialist apologetics,”an ironic claim, since I am not an evidentialist, and the topic of the debate was determined by Ehrman’s published claims. It was not a debate on the existence of God or even the theological possibility of divine revelation. Further, I will respond fully to the implication of Mr. McDurmon’s words that I somehow claimed, or believe, that “manuscript evidence forms the basis of our trust in the veracity of Scripture”outside of the work of the Spirit in bringing one to conviction of the truth of God’s Word.

James White